US Senator John McCain , Kim Âu Hà văn Sơn

NT Kiên , UCV Bob Barr, Kim Âu Hà văn Sơn

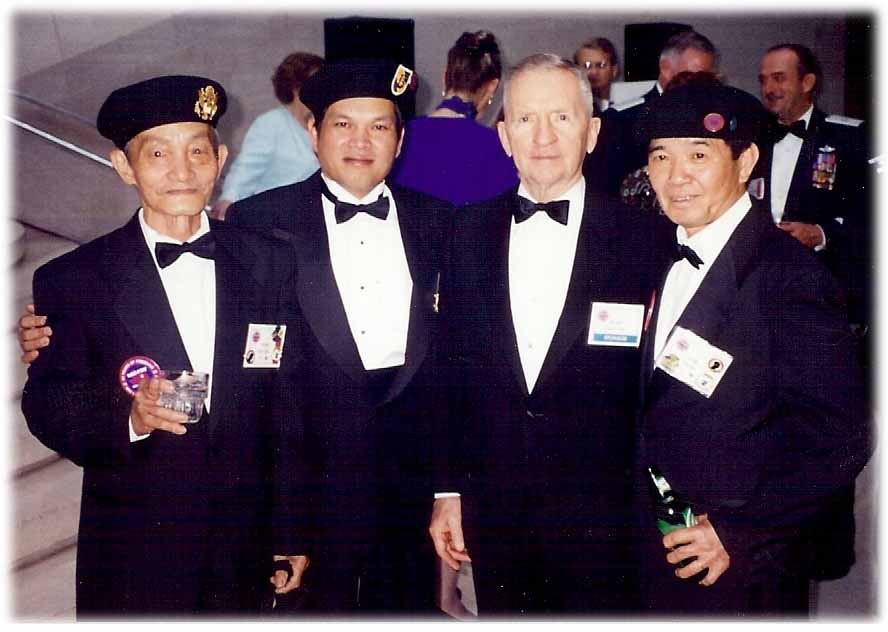

Nguyễn Thái Kiên , Kim Âu Hà văn Sơn, Cố vấn an ninh đặc biệt của Reagan-Tỷ phú Ross Perot,Trình A Sám

How Does a Bill Become Law?

The chief function of Congress is the making of laws. A very brief overview of the legislative process within the House of Representatives is presented below. There are many aspects and variations of the process which are not addressed here. A much more in-depth discussion and presentation of the overall process is available in How Our Laws Are Made. Most of the information presented below was excerpted from that Congressional document.

Forms of Congressional Action

The work of Congress is initiated by the introduction of a proposal in one of four principal forms: the bill, the joint resolution, the concurrent resolution, and the simple resolution.

Bills

A bill is the form used for most legislation, whether permanent or temporary, general or special, public or private. A bill originating in the House of Representatives is designated by the letters "H.R.", signifying "House of Representatives", followed by a number that it retains throughout all its parliamentary stages. Bills are presented to the President for action when approved in identical form by both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Joint Resolutions

Joint resolutions may originate either in the House of Representatives or in the Senate. There is little practical difference between a bill and a joint resolution. Both are subject to the same procedure, except for a joint resolution proposing an amendment to the Constitution. On approval of such a resolution by two-thirds of both the House and Senate, it is sent directly to the Administrator of General Services for submission to the individual states for ratification. It is not presented to the President for approval. A joint resolution originating in the House of Representatives is designated "H.J.Res." followed by its individual number. Joint resolutions become law in the same manner as bills.

Concurrent Resolutions

Matters affecting the operations of both the House of Representatives and Senate are usually initiated by means of concurrent resolutions. A concurrent resolution originating in the House of Representatives is designated "H.Con.Res." followed by its individual number. On approval by both the House of Representatives and Senate, they are signed by the Clerk of the House and the Secretary of the Senate. They are not presented to the President for action.

Simple Resolutions

A matter concerning the operation of either the House of Representatives or Senate alone is initiated by a simple resolution. A resolution affecting the House of Representatives is designated "H.Res." followed by its number. They are not presented to the President for action.

For more information on bills and resolutions see Forms of Congressional Action in How Our Laws Are Made.

Introduction and Referral to Committee

Any Member in the House of Representatives may introduce a bill at any time while the House is in session by simply placing it in the "hopper" provided for the purpose at the side of the Clerk's desk in the House Chamber. The sponsor's signature must appear on the bill. A public bill may have an unlimited number of co-sponsoring Members. The bill is assigned its legislative number by the Clerk and referred to the appropriate committee by the Speaker, with the assistance of the Parliamentarian. The bill is then printed in its introduced form, which you can read in Bill Text. If a bill was introduced today, summary information about it can be found in Bill Status Today.

An important phase of the legislative process is the action taken by committees. It is during committee action that the most intense consideration is given to the proposed measures; this is also the time when the people are given their opportunity to be heard. Each piece of legislation is referred to the committee that has jurisdiction over the area affected by the measure.

For more information on this step of the legislative process see Introduction and Reference to Committee of How Our Laws Are Made.

Consideration by Committee

Public Hearings and Markup Sessions

Usually the first step in this process is a public hearing, where the committee members hear witnesses representing various viewpoints on the measure. Each committee makes public the date, place and subject of any hearing it conducts. The Committee Meetings scheduled for today are available along with other House Schedules . Public announcements are also published in the Daily Digest portion of the Congressional Record.

A transcript of the testimony taken at a hearing is made available for inspection in the committee office, and frequently the complete transcript is printed and distributed by the committee.

After hearings are completed, the bill is considered in a session that is popularly known as the "mark-up" session. Members of the committee study the viewpoints presented in detail. Amendments may be offered to the bill, and the committee members vote to accept or reject these changes.

This process can take place at either the subcommittee level or the full committee level, or at both. Hearings and markup sessions are status steps noted in the Legislative Action portion of Bill Status.

Committee Action

At the conclusion of deliberation, a vote of committee or subcommittee Members is taken to determine what action to take on the measure. It can be reported, with or without amendment, or tabled, which means no further action on it will occur. If the committee has approved extensive amendments, they may decide to report a new bill incorporating all the amendments. This is known as a "clean bill," which will have a new number. Votes in committee can be found in Committee Votes.

If the committee votes to report a bill, the Committee Report is written. This report describes the purpose and scope of the measure and the reasons for recommended approval. House Report numbers are prefixed with "H.Rpt." and then a number indicating the Congress (currently 107).

For more information on bills and resolutions see Consideration by Committee in How Our Laws Are Made.

House Floor Consideration

Consideration of a measure by the full House can be a simple or very complex operation. In general a measure is ready for consideration by the full House after it has been reported by a committee. Under certain circumstances, it may be brought to the Floor directly.

The consideration of a measure may be governed by a "rule." A rule is itself a simple resolution, which must be passed by the House, that sets out the particulars of debate for a specific bill—how much time will allowed for debate, whether amendments can be offered, and other matters.

Debate time for a measure is normally divided between proponents and opponents. Each side yields time to those Members who wish to speak on the bill. When amendments are offered, these are also debated and voted upon. If the House is in session today, you can see a summary of Current House Floor Proceedings .

After all debate is concluded and amendments decided upon, the House is ready to vote on final passage. In some cases, a vote to "recommit" the bill to committee is requested. This is usually an effort by opponents to change some portion or table the measure. If the attempt to recommit fails, a vote on final passage is ordered.

Resolving Differences

After a measure passes in the House, it goes to the Senate for consideration. A bill must pass both bodies in the same form before it can be presented to the President for signature into law.

If the Senate changes the language of the measure, it must return to the House for concurrence or additional changes. This back-and-forth negotiation may occur on the House floor, with the House accepting or rejecting Senate amendments or complete Senate text. Often a conference committee will be appointed with both House and Senate members. This group will resolve the differences in committee and report the identical measure back to both bodies for a vote. Conference committees also issue reports outlining the final version of the bill.

Final Step

Votes on final passage, as well as all other votes in the House, may be taken by the electronic voting system which registers each individual Member's response. These votes are referred to as Yea/Nay votes or recorded votes, and are available in House Votes by Bill number, roll call vote number or words describing the reason for the vote.

Votes in the House may also be by voice vote, and no record of individual responses is available.

After a measure has been passed in identical form by both the House and Senate, it is considered "enrolled." It is sent to the President who may sign the measure into law, veto it and return it to Congress, let it become law without signature, or at the end of a session, pocket-veto it.

From U.S. House of Representatives Educational Resources, Tying it All Together

HOW OUR LAWS ARE MADE

Revised and Updated

By John V. Sullivan, Parliamentarian,

U.S. House of Representatives

Presented by Mr. Brady of Pennsylvania

July 24, 2007.—Ordered to be printed

(II)

H. Con. Res. 190 Agreed to July 25, 2007

One Hundred Tenth Congress

of the

United States of America

AT THE FIRST SESSION

Begun and held at the City of Washington on Thursday, the fourth day of January, two thousand and seven Concurrent Resolution Resolved by the House of Representatives (the Senate concurring),

SECTION 1. HOW OUR LAWS ARE MADE.

(a)IN GENERAL.—An edition of the brochure entitled ‘‘How Our Laws Are Made’’, as revised under the direction of the Parliamentarian of the House of Representatives in consultation with the Parliamentarian of the Senate, shall be printed as a House document under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing.

(b) ADDITIONAL COPIES.—In addition to the usual number, there shall be printed the lesser of—

(1) 550,000 copies of the document, of which 440,000 copies shall be for the use of the House of Representatives, 100,000 copies shall be for the use of the Senate, and 10,000 copies shall be for the use of the Joint Committee on Printing; or (2) such number of copies of the document as does not exceed a total production and printing cost of $479,247, with distribution to be allocated in the same proportion as described in paragraph (1), except that in no case shall the number of copies be less than 1 per Member of Congress.

Attest:

LORRAINE C. MILLER,

Clerk of the House of Representatives.

Attest:

NANCY ERICKSON

Secretary of the Senate.

(III)

EARLIER PRINTINGS

Number

Document of copies

1953, H. Doc. 210, 83d Cong. (H. Res. 251 by Mr. Reed) 36,771

1953, H. Doc. 210, 83d Cong. (H. Res. 251 by Mr. Reed) 122,732

1955, H. Doc. 210, 83d Cong. (H. Con. Res. 93 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 167,728

1956, H. Doc. 451, 84th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 251 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 30,385

1956, S. Doc. 152, 84th Cong. (S. Res. 293 by Senator

Kennedy) .......................................................................... 182,358

1959, H. Doc. 156, 86th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 95 by Mr.

Lesinski) ........................................................................... 228,591

1961, H. Doc. 136, 87th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 81 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 211,797

1963, H. Doc. 103, 88th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 108 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 14,000

1965, H. Doc. 103, 88th Cong. (S. Res. 9 by Senator

Mansfield) ......................................................................... 196,414

1965, H. Doc. 164, 89th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 165 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 319,766

1967, H. Doc. 125, 90th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 221 by Mr.

Willis) ............................................................................... 324,821

1969, H. Doc. 127, 91st Cong. (H. Con. Res. 192 by Mr.

Celler) ............................................................................... 174,500

1971, H. Doc. 144, 92d Cong. (H. Con. Res. 206 by Mr.

Celler) ............................................................................... 292,000

1972, H. Doc. 323, 92d Cong. (H. Con. Res. 530 by Mr.

Celler) ............................................................................... 292,500

1974, H. Doc. 377, 93d Cong. (H. Con. Res. 201 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 246,000

1976, H. Doc. 509, 94th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 540 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 282,400

1978, H. Doc. 259, 95th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 190 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 298,000

1980, H. Doc. 352, 96th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 95 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 298,000

1981, H. Doc. 120, 97th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 106 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 298,000

1985, H. Doc. 158, 99th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 203 by Mr.

Rodino) .............................................................................. 298,000

VerDate Aug 31 2005 07:44 Mar 19, 2008 Jkt 036931 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 7633 Sfmt 6664 E:\TEMP\HD049C.XXX PRFM99 PsN: HD049C bjneal on GSDDPC74 with HEARING

IV

Number

Document of copies

1989, H. Doc. 139, 101st Cong. (H. Con. Res. 193 by Mr.

Brooks) .............................................................................. 323,000

1997, H. Doc. 14, 105th Cong. (S. Con. Res. 62 by Senator

Warner) .................................................................... 387,000

2000, H. Doc. 197, 106th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 221 by Mr.

Thomas) ............................................................................ 550,000

2003, H. Doc. 93, 108th Cong. (H. Con. Res. 139 by Mr.

Ney) ................................................................................... 550,000

(V)

FOREWORD

First published in 1953 by the Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives, this 24th edition of ‘‘How Our Laws Are Made’’ reflects changes in congressional procedures since the 23rd edition, which was revised and updated in 2003. This edition was prepared by the Office of the Parliamentarian of the U.S. House of Representatives in consultation with the Office of the Parliamentarian of the U.S. Senate. The framers of our Constitution created a strong federal government resting on the concept of ‘‘separation of powers.’’ In Article I, Section 1, of the Constitution, the Legislative Branch is created by the following language: ‘‘All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.’’ Article I, Section 5, of the Constitution provides that: ‘‘Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, . . .’’.

Upon this elegant, yet simple, grant of legislative powers and rulemaking authority has grown an exceedingly complex and evolving legislative process—much of it unique to each House of Congress. To aid the public’s understanding of the legislative process, we have revised this popular brochure. For more detailed information on how our laws are made and for the text of the laws themselves, the reader should refer to government internet sites or pertinent House and Senate publications available from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402.

JOHN V. SULLIVAN.

(VII)

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Page

I. Introduction .................................................................... 1

II. The Congress .................................................................. 1

III. Sources of Legislation .................................................... 4

IV. Forms of Congressional Action ...................................... 5

Bills ............................................................................ 5

Joint Resolutions ....................................................... 6

Concurrent Resolutions ............................................ 7

Simple Resolutions .................................................... 8

V. Introduction and Referral to Committee ...................... 8

VI. Consideration by Committee ......................................... 11

Committee Meetings ................................................. 11

Public Hearings ......................................................... 12

Markup ....................................................................... 14

Final Committee Action ............................................ 14

Points of Order With Respect to Committee Hearing

Procedure ..................................................... 15

VII. Reported Bills ................................................................. 15

Contents of Reports ................................................... 16

Filing of Reports ........................................................ 18

Availability of Reports and Hearings ...................... 18

VIII. Legislative Oversight by Standing Committees ........... 18

IX. Calendars ........................................................................ 19

Union Calendar ......................................................... 19

House Calendar ......................................................... 20

Private Calendar ....................................................... 20

Calendar of Motions to Discharge Committees ...... 20

X. Obtaining Consideration of Measures .......................... 20

Unanimous Consent .................................................. 21

Special Resolution or ‘‘Rule’’ ..................................... 21

Consideration of Measures Made in Order by Rule

Reported From the Committee on Rules .......... 22

Motion to Discharge Committee .............................. 22

Motion to Suspend the Rules ................................... 23

Calendar Wednesday ................................................ 24

District of Columbia Business .................................. 24

Questions of Privilege ............................................... 24

VerDate Aug 31 2005 07:44 Mar 19, 2008 Jkt 036931 PO 00000 Frm 00007 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 0581 E:\TEMP\HD049C.XXX PRFM99 PsN: HD049C bjneal on GSDDPC74 with HEARING

Page

VIII

Privileged Matters ..................................................... 25

XI. Consideration and Debate ............................................. 25

Committee of the Whole ........................................... 26

Second Reading ......................................................... 27

Amendments and the Germaneness Rule ............... 28

Congressional Earmarks .......................................... 28

The Committee ‘‘Rises’’ ............................................. 28

House Action .............................................................. 29

Motion to Recommit .................................................. 29

Quorum Calls and Rollcalls ...................................... 30

Voting ......................................................................... 31

Electronic Voting ....................................................... 33

Pairing of Members ................................................... 33

System of Lights and Bells ....................................... 33

Recess Authority ....................................................... 34

Live Coverage of Floor Proceedings ......................... 34

XII. Congressional Budget Process ....................................... 35

XIII. Engrossment and Message to Senate ........................... 36

XIV. Senate Action .................................................................. 37

Committee Consideration ......................................... 37

Chamber Procedure .................................................. 38

XV. Final Action on Amended Bill ....................................... 41

Request for a Conference .......................................... 42

Authority of Conferees .............................................. 43

Meetings and Action of Conferees ........................... 44

Conference Reports ................................................... 46

Custody of Papers ..................................................... 48

XVI. Bill Originating in Senate .............................................. 49

XVII. Enrollment ...................................................................... 49

XVIII. Presidential Action ......................................................... 50

Veto Message ............................................................. 51

Line Item Veto ........................................................... 52

XIX. Publication ...................................................................... 52

Slip Laws ................................................................... 53

Statutes at Large ...................................................... 53

United States Code ................................................... 54

Appendix ...................................................................................... 55

(1)

HOW OUR LAWS ARE MADE

I.INTRODUCTION

This brochure is intended to provide a basic outline of the numerous steps of our federal lawmaking process from the source of an idea for a legislative proposal through its publication as a statute. The legislative process is a matter about which every person should be well informed in order to understand and appreciate the work of Congress. It is hoped that this guide will enable readers to gain a greater understanding of the federal legislative process and its role as one of the foundations of our representative system. One of the most practical safeguards of the American democratic way of life is this legislative process with its emphasis on the protection of the minority, allowing ample opportunity to all sides to be heard and make their views known. The fact that a proposal cannot become a law without consideration and approval by both Houses of Congress is an outstanding virtue of our bicameral legislative system. The open and full discussion provided under the Constitution often results in the notable improvement of a bill by amendment before it becomes law or in the eventual defeat of an inadvisable proposal.

As the majority of laws originate in the House of Representatives, this discussion will focus principally on the procedure in that body.

II. THE CONGRESS

Article I, Section 1, of the United States Constitution, provides that:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

The Senate is composed of 100 Members—two from each state, regardless of population or area—elected by the people in accordance with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution. The 17th Amendment changed the former constitutional method under which Senators were chosen by the respective state legislatures. ASenator must be at least 30 years of age, have been a citizen of the United States for nine years, and, when elected, be an inhabitant of the state for which the Senator is chosen. The term of office is six years and one-third of the total membership of the Senate is elected every second year. The terms of both Senators from a particular state are arranged so that they do not terminate at the same time. Of the two Senators from a state serving at the same time the one who was elected first—or if both were elected at the same time, the one elected for a full term—is referred to as the ‘‘senior’’ Senator from that state. The other is referred to as the ‘‘junior’’ Senator. If a Senator dies or resigns during the term, the governor of the state must call a special election unless the state legislature has authorized the governor to appoint a successor until the next election, at which time a successor is elected for the balance of the term. Most of the state legislatures have granted their governors the power of appointment.

Each Senator has one vote.

As constituted in the 110th Congress, the House of Representatives is composed of 435 Members elected every two years from among the 50 states, apportioned to their total populations. The permanent number of 435 was established by federal law following the Thirteenth Decennial Census in 1910, in accordance with Article

I, Section 2, of the Constitution. This number was increased temporarily to 437 for the 87th Congress to provide for one Representative each for Alaska and Hawaii. The Constitution limits the number of Representatives to not more than one for every 30,000 of population. Under a former apportionment in one state, a particular Representative represented more than 900,000 constituents, while another in the same state was elected from a district having a population of only 175,000. The Supreme Court has since held unconstitutional a Missouri statute permitting a maximum population variance of 3.1 percent from mathematical equality.

The Court ruled in Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394 U.S. 526 (1969), that the variances among the districts were not unavoidable and, therefore, were invalid. That decision was an interpretation of the Court’s earlier ruling in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964), that the Constitution requires that ‘‘as nearly as is practicable one man’s vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another’s.’’

A law enacted in 1967 abolished all ‘‘at-large’’ elections except in those less populous states entitled to only one Representative. An ‘‘at-large’’ election is one in which a Representative is elected by the voters of the entire state rather than by the voters in a congressional district within the state. A Representative must be at least 25 years of age, have been a citizen of the United States for seven years, and, when elected, be an inhabitant of the state in which the Representative is chosen.

Unlike the Senate where a successor may be appointed by a governor when a vacancy occurs during a term, if a Representative dies or resigns during the term, the executive authority of the state must call a special election pursuant to state law for the choosing of a successor to serve for the unexpired portion of the term. Each Representative has one vote. In addition to the Representatives from each of the States, a Resident Commissioner from the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and Delegates from the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, and the Virgin Islands are elected pursuant to federal law. The Resident Commissioner, elected for a four-year term, and the Delegates, elected for two-year terms, have most of the prerogatives of Representatives including the right to vote in committees to which they are elected, the right to vote in the Committee of the Whole (subject to an automatic revote in the House whenever a recorded vote has been decided by a margin within which the votes

cast by the Delegates and the Resident Commissioner have been decisive), and the right to preside over the Committee of the Whole. However, the Resident Commissioner and the Delegates do not have the right to vote on matters before the House. Under the provisions of Section 2 of the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, Congress must assemble at least once every year, at noon on the third day of January, unless by law they appoint a different day.

A Congress lasts for two years, commencing in January of the year following the biennial election of Members.

A Congress is divided into two regular sessions.

The Constitution authorizes each House to determine the rules of its proceedings. Pursuant to that authority, the House of Representatives adopts its rules anew each Congress, ordinarily on the opening day of the first session. The Senate considers itself a continuing body and operates under continuous standing rules that it amends from time to time. Unlike some other parliamentary bodies, both the Senate and the House of Representatives have equal legislative functions and powers with certain exceptions. For example, the Constitution provides that only the House of Representatives may originate revenue bills.

By tradition, the House also originates appropriation bills. As both bodies have equal legislative powers, the designation of one as the ‘‘upper’’ House and the other as the ‘‘lower’’ House is not applicable. The chief function of Congress is the making of laws. In addition, the Senate has the function of advising and consenting to treaties and to certain nominations by the President. Under the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, a vote in each House is required to confirm the President’s nomination for Vice-President when there is a vacancy in that office. In the matter of impeachments, the House of Representatives presents the charges—a function similar to that of a grand jury—and the Senate sits as a court to try the impeachment. No impeached person may be removed without a two-thirds vote of those Senators voting, a quorum being present. The Congress under the Constitution and by statute also plays a role in presidential elections. Both Houses meet in joint session on the sixth day of January following a presidential election, unless by law they appoint a different day, to count the electoralvotes. If no candidate receives a majority of the total electoral votes, the House of Representatives, each state delegation having one vote, chooses the President from among the three candidates having the largest number of electoral votes. The Senate, each Senator having one vote, chooses the Vice President from the two candidates having the largest number of votes for that office.

III. SOURCES OF LEGISLATION

Sources of ideas for legislation are unlimited and proposed drafts of bills originate in many diverse quarters. Primary among these is the idea and draft conceived by a Member. This may emanate from the election campaign during which the Member had promised, if elected, to introduce legislation on a particular subject. The Member may have also become aware after taking office of the need for amendment to or repeal of an existing law or the enactment of a statute in an entirely new field. In addition, the Member’s constituents, either as individuals or

through citizen groups, may avail themselves of the right to petition and transmit their proposals to the Member. The right to petition is guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution. Similarly, state legislatures may ‘‘memorialize’’ Congress to enact specified federal laws by passing resolutions to be transmitted to the House and Senate as memorials. If favorably impressed by the idea, a Member may introduce the proposal in the form in which it has been submitted or may redraft it. In any event, a Member may consult with the Legislative Counsel of the House or the Senate to frame the ideas in suitable legislative language and form.

In modern times, the ‘‘executive communication’’ has become a prolific source of legislative proposals. The communication is usually in the form of a message or letter from a member of the President’s Cabinet, the head of an independent agency, or the President himself, transmitting a draft of a proposed bill to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President of the Senate.

Despite the structure of separation of powers, Article II, Section 3, of the Constitution imposes an obligation on the President to report to Congress from time to time on the ‘‘State of the Union’’ and to recommend for consideration such measures as the President considers necessary and expedient. Many of these executive communications follow on the President’s message to Congress on the state of the Union. The communication is then referred to the standing committee or committees having jurisdiction of the subject matter of the proposal. The chairman or the ranking minority member of the relevant committee often introduces the bill, either in the form in which it was received or with desired changes. This practice is usually followed even when the majority of the House and the President are not of the same political party, although there is no constitutional or statutory requirement that a bill be introduced to effectuate the recommendations.

The most important of the regular executive communications is the annual message from the President transmitting the proposed budget to Congress. The President’s budget proposal, together with testimony by officials of the various branches of the government before the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate, is

the basis of the several appropriation bills that are drafted by the Committees on Appropriations of the House and Senate. The drafting of statutes is an art that requires great skill, knowledge, and experience. In some instances, a draft is the result of a study covering a period of a year or more by a commission or committee designated by the President or a member of the Cabinet. The Administrative Procedure Act and the Uniform Code of Military Justice are two examples of enactments resulting from such studies. In addition, congressional committees sometimes draft bills after studies and hearings covering periods of a year or more.

IV. FORMS OF CONGRESSIONAL ACTION

The work of Congress is initiated by the introduction of a proposal in one of four forms: the bill, the joint resolution, the concurrent resolution, and the simple resolution. The most customary form used in both Houses is the bill. During the 109th Congress (2005–2006), 10,558 bills and 143 joint resolutions were introduced in both Houses. Of the total number introduced, 6,436 bills and 102 joint resolutions originated in the House of Representatives.

For the purpose of simplicity, this discussion will be confined generally to the procedure on a measure of the House of Representatives, with brief comment on each of the forms.

BILLS

A bill is the form used for most legislation, whether permanent or temporary, general or special, public or private.

The form of a House bill is as follows:

A BILL

For the establishment, etc. [as the title may be].

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That, etc.

The enacting clause was prescribed by law in 1871 and is identical in all bills, whether they originate in the House of Representatives or in the Senate.

Bills may originate in either the House of Representatives or the Senate with one notable exception. Article I, Section 7, of the Constitution provides that all bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives but that the Senate may propose, or concur with, amendments. By tradition, general appropriation

bills also originate in the House of Representatives. There are two types of bills—public and private. A public bill is one that affects the public generally. A bill that affects a specified individual or a private entity rather than the population at large is called a private bill. A typical private bill is used for relief in matters such as immigration and naturalization and claims against the United States.

A bill originating in the House of Representatives is designated by ‘‘H.R.’’ followed by a number that it retains throughout all its parliamentary stages. The letters signify ‘‘House of Representatives’’ and not, as is sometimes incorrectly assumed, ‘‘House resolution.’’ A Senate bill is designated by ‘‘S.’’ followed by its number. The term ‘‘companion bill’’ is used to describe a bill introduced in one House of Congress that is similar or identical to a bill introduced in the other House of Congress. A bill that has been agreed to in identical form by both bodies

becomes the law of the land only after—

(1) Presidential approval; or

(2) failure by the President to return it with objections to the House in which it originated within 10 days (Sundays excepted) while Congress is in session; or

(3) the overriding of a presidential veto by a two-thirds vote in each House.

Such a bill does not become law without the President’s signature if Congress by their final adjournment prevent its return with objections. This is known as a ‘‘pocket veto.’’ For a discussion of presidential action on legislation, see Part XVIII.

JOINT RESOLUTIONS

Joint resolutions may originate either in the House of Representatives or in the Senate—not, as is sometimes incorrectly assumed, jointly in both Houses. There is little practical difference between a bill and a joint resolution and the two forms are sometimes used interchangeably. One difference in form is that a joint resolution may include a preamble preceding the resolving clause. Statutes that have been initiated as bills may be amended by a joint resolution and vice versa. Both are subject to the same procedure except for a joint resolution proposing an amendment to the Constitution. When a joint resolution amending the Constitution is approved by two-thirds of both Houses, it is not presented to the President for approval. Rather, such a joint resolution is sent directly to the Archivist of the United States for submission to the several states where ratification by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states within the period of time prescribed in the joint resolution is necessary for the amendment to become part of the Constitution.

The form of a House joint resolution is as follows:

JOINT RESOLUTION

Authorizing, etc. [as the title may be].

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That, etc.

The resolving clause is identical in both House and Senate joint resolutions as has been prescribed by statute since 1871. It is frequently preceded by a preamble consisting of one or more ‘‘whereas’’ clauses indicating the necessity for or the desirability of the joint resolution.

A joint resolution originating in the House of Representatives is designated ‘‘H.J. Res.’’ followed by its individual number which it retains throughout all its parliamentary stages. One originating in the Senate is designated ‘‘S.J. Res.’’ followed by its number. Joint resolutions, with the exception of proposed amendments to the Constitution, become law in the same manner as bills.

CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS

A matter affecting the operations of both Houses is usually initiated by a concurrent resolution. In modern practice, and as determined by the Supreme Court in INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983), concurrent and simple resolutions normally are not legislative in character since not ‘‘presented’’ to the President for approval, but are used merely for expressing facts, principles, opinions, and purposes of the two Houses. A concurrent resolution is not equivalent to a bill and its use is narrowly limited within these bounds. The term ‘‘concurrent’’, like ‘‘joint’’, does not signify simultaneous introduction and consideration in both Houses. A concurrent resolution originating in the House of Representatives is designated ‘‘H. Con. Res.’’ followed by its individual number, while a Senate concurrent resolution is designated ‘‘S. Con. Res.’’ together with its number. On approval by both Houses, they are signed by the Clerk of the House and the Secretary of the Senate and transmitted to the Archivist of the United States for publication in a special part of the Statutes at Large volume covering that session of Congress.

SIMPLE RESOLUTIONS

A matter concerning the rules, the operation, or the opinion of either House alone is initiated by a simple resolution. A resolution affecting the House of Representatives is designated ‘‘H. Res.’’ Followed by its number, while a Senate resolution is designated ‘‘S. Res.’’ together with its number. Simple resolutions are considered only by the body in which they were introduced. Upon adoption, simple resolutions are attested to by the Clerk of the House of Representatives or the Secretary of the Senate and are published in the Congressional Record.

V. INTRODUCTION AND REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE

Any Member, Delegate or the Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico in the House of Representatives may introduce a bill at any time while the House is in session by simply placing it in the ‘‘hopper,’’ a wooden box provided for that purpose located on the side of the rostrum in the House Chamber. Permission is not required to introduce the measure. The Member introducing the bill is known as the primary sponsor. Except in the case of private bills, an unlimited number of Members may cosponsor a bill. To prevent the possibility that a bill might be introduced in the House on behalf of a Member without that Member’s prior approval, the primary sponsor’s signature must appear on the bill before it is accepted for introduction. Members who cosponsor a bill upon its date of introduction are original cosponsors. Members who cosponsor a bill after its introduction are additional cosponsors. Cosponsors are not required to sign the bill. A Member may not be added or deleted as a cosponsor after the bill has been reported by, or discharged from, the last committee authorized to consider it, and the Speaker may not entertain a request to delete the name of the primary sponsor at any time. Cosponsors’ names may be deleted by their own unanimous-consent request or that of the primary sponsor. In the Senate, unlimited multiple sponsorship of a bill is permitted. A Member may insert the words ‘‘by request’’ after the Member’s name to indicate that the introduction of the measure is at the suggestion of some other person or group—usually the President or a member of his Cabinet. In the Senate, a Senator usually introduces a bill or resolution by presenting it to one of the clerks at the Presiding Officer’s desk, without commenting on it from the floor of the Senate. However, a Senator may use a more formal procedure by rising and introducing the bill or resolution from the floor, usually accompanied by a statement about the measure. Frequently, Senators obtain consent to have the bill or resolution printed in the Congressional Record following their formal statement. In the House of Representatives, it is no longer the custom to read bills—even by title—at the time of introduction. The title is

entered in the Journal and printed in the Congressional Record, thus preserving the purpose of the custom. The bill is assigned its legislative number by the Clerk. The bill is then referred as required by the rules of the House to the appropriate committee or committees by the Speaker, with the assistance of the Parliamentarian. The bill number and committee referral appear in the next issue of the Congressional Record. It is then sent to the Government Printing Office where it is printed and copies are made available in the document rooms of both Houses. Printed and electronic versions of the bill are also made available to the public. Copies of the bill are sent to the office of the chairman of each committee to which it has been referred. The clerk of the committee enters it on the committee’s Legislative Calendar. Perhaps the most important phase of the legislative process is the action by committees. The committees provide the most intensive consideration to a proposed measure as well as the forum where the public is given their opportunity to be heard. A tremendous volume of work, often overlooked by the public, is done by the Members in this phase. There are, at present, 20 standing committees in the House and 16 in the Senate as well as several select committees. In addition, there are four standing joint committees of the two Houses, with oversight responsibilities but no legislative jurisdiction. The House may also create select committees or task forces to study specific issues and report on them to the House. A task force may be established formally through a resolution passed by the House or informally through organization of interested Members by the House leadership. Each committee’s jurisdiction is defined by certain subject matter under the rules of each House and all measures are referred accordingly.

For example, the Committee on the Judiciary in the House has jurisdiction over measures relating to judicial proceedings and 18 other categories, including constitutional amendments, immigration policy, bankruptcy, patents, copyrights, and trademarks. In total, the rules of the House and of the Senate each provide for over 200 different classifications of measures to be referred to committees. Until 1975, the Speaker of the House could refer a bill to only one committee. In modern practice, the Speaker may refer an introduced bill to multiple committees for consideration of those provisions of the bill within the jurisdiction of eachcommittee concerned. Except in extraordinary circumstances, the Speaker must designate a primary committee of jurisdiction on bills referred to multiple committees. The Speaker may place time limits on the consideration of bills by all committees, but usually time limits are placed only on additional committees to which a bill has been referred following the report of the primary committee.

In the Senate, introduced measures and House-passed measures are referred to the one committee of preponderant jurisdiction by the Parliamentarian on behalf of the Presiding Officer. By special or standing order, a measure may be referred to more than one committee in the Senate. Membership on the various committees is divided between the two major political parties. The proportion of the Members of the minority party to the Members of the majority party is determined by the majority party, except that half of the members on the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct are from the majority party and half from the minority party. The respective party caucuses nominate Members of the caucus to be elected to each standing committee at the beginning of each Congress. Membership on a standing committee during the course of a Congress is contingent on continuing membership in the party caucus that nominated a Member for election to the committee. If a Member ceases to be a Member of the party caucus, a Member automatically ceases to be a member of the standing committee. Members of the House may serve on only two committees and four subcommittees with certain exceptions. However, the rules of the caucus of the majority party in the House provide that a Member may be chairman of only one subcommittee of a committee or select committee with legislative jurisdiction, except for certain committees performing housekeeping functions and joint committees. A Member usually seeks election to the committee that has jurisdiction over a field in which the Member is most qualified and interested.

For example, the Committee on the Judiciary traditionally is populated with numerous lawyers. Members rank in seniority in accordance with the order of their appointment to the full committee and the ranking majority member with the most continuous service is often elected chairman. The rules of the House require that committee chairmen be elected from nominations submitted by the majority party caucus at the commencement of each Congress. No Member of the House may serve as chairman of the same standing committee or of the same subcommittee thereof for more than three consecutive Congresses, except in the case of the Committee on Rules. The rules of the House provide that a committee may maintain no more than five committees, but may have an oversight committee as a sixth. The standing rules allow a greater number of subcommittees for the Committees on Appropriations and Oversight and Government Reform. In addition, the House may grant leave to certain committeess to establish additional subcommittees during a given Congress. Each committee is provided with a professional staff to assist it in the innumerable administrative details involved in the consideration of bills and its oversight responsibilities. For standing committees,the professional staff is limited to 30 persons appointed by a vote of the committee. Two-thirds of the committee staff are selected by a majority vote of the majority committee members and one-third of the committee staff are selected by a majority vote of minority committee members. All staff appointments are made without regard to race, creed, sex, or age. Minority staff requirements do not apply to the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct because of its bipartisan nature. The Committee on Appropriations has special authority under the rules of the House for appointment of staff for the minority.

VI. CONSIDERATION BY COMMITTEE

One of the first actions taken by a committee is to seek the input of the relevant departments and agencies about a bill. Frequently, the bill is also submitted to the Government Accountability Office with a request for an official report of views on the necessity or desirability of enacting the bill into law. Normally, ample time is given for the submission of the reports and they are accorded serious consideration. However, these reports are not binding on the committee in determining whether or not to act favorably on the bill. Reports of the departments and agencies in the executive branch are submitted first to the Office of Management and Budget to determine whether they are consistent with the program of the President. Many committees adopt rules requiring referral of measures to the appropriate subcommittee unless the full committee votes to retain the measure at the full committee.

COMMITTEE MEETINGS

Standing committees are required to have regular meeting days at least once a month. The chairman of the committee may also call and convene additional meetings. Three or more members of a standing committee may file with the committee a written request that the chairman call a special meeting. The request must specify the measure or matter to be considered. If the chairman does not schedule the requested special meeting within three calendar days after the filing of the request, to be held within seven calendar days after the filing of the request, a majority of the members of the committee may call the special meeting by filing with the committee written notice specifying the date, hour, and the measure or matter to be considered at the meeting. In the Senate, the Chair may still control the agenda of the special meeting through the power of recognition. Committee meetings may be held for various purposes including the ‘‘markup’’ of legislation, authorizing subpoenas, or internal budget and personnel matters. A subpoena may be authorized and issued at a meeting by a vote of a committee or subcommittee with a majority of members present. The power to authorize and issue subpoenas also may be delegated to the chairman of the committee. A subpoena may require both testimonial and documentary evidence to be furnished to the committee. A subpoena is signed by the chairman of the committee or by a member designated by the committee. All meetings for the transaction of business of standing committees or subcommittees, except the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, must be open to the public, except when the committee or subcommittee, in open session with a majority present, determines by record vote that all or part of the remainder of the meeting on that day shall be closed to the public. Members of the committee may authorize congressional staff and departmental representatives to be present at any meeting that has been closed to the public. Open committee meetings may be covered by the media. Permission to cover hearings and meetings is granted under detailed conditions as provided in the rules of the House. The rules of the House provide that House committees may not meet during a joint session of the House and Senate or during a recess when a joint meeting of the House and Senate is in progress. Committees may meet at other times during an adjournment or recess up to the expiration of the constitutional term. The rules of the Senate provide that Senate committees may not meet after two hours after the meeting of the Senate commenced, and in no case after 2 p.m. when the Senate is in session. Special leave for this purpose may be granted by the Majority and Minority leaders.

PUBLIC HEARINGS

If the bill is of sufficient importance, the committee may set a date for public hearings. The chairman of each committee, except for the Committee on Rules, is required to make public announcement of the date, place, and subject matter of any hearing at least one week before the commencement of that hearing, unless the committee chairman with the concurrence of the ranking minority member or the committee by majority vote determines that there is good cause to begin the hearing at an earlier date. If that determination is made, the chairman must make a public announcement to that effect at the earliest possible date. Public announcements are published in the Daily Digest portion of the Congressional Record as soon as possible after an announcement is made and are often noted by the media. Personal notice of the hearing, usually in the form of a letter, is sometimes sent to relevant individuals, organizations, and government departments and agencies. Each hearing by a committee or subcommittee, except the Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, is required to be open to the public except when the committee or subcommittee, in open session and with a majority present, determines by record vote that all or part of the remainder of the hearing on that day shall be closed to the public because disclosure of testimony, evidence, or other matters to be considered would endanger national security, would compromise sensitive law enforcement information, or would violate a law or a rule of the House. The committee or subcommittee may by the same procedure vote to close one subsequent day of hearing, except that the Committees on Appropriations, Armed Services, and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and subcommittees thereof, may vote to close up to five additional, consecutive days of hearings. When a quorum for taking testimony is present, a majority of the members present may close a hearing to discuss whether the evidence or testimony to be received would endanger national security or would tend to defame, degrade, or incriminate any person. A committee or subcommittee may vote to release or make public matters originally received in a closed hearing or meeting. Open committee hearings may be covered by the media. Permission to cover hearings and meetings is granted under detailed conditions as provided in the rules of the House. Hearings on the President’s Budget are required to be held by the Committee on Appropriations in open session within 30 days after its transmittal to Congress, except when the committee, in open session and with a quorum present, determines by record vote that the testimony to be taken at that hearing on that day may be related to a matter of national security. The committee may by the same procedure close one subsequent day of hearing.

On the day set for a public hearing in a committee or subcommittee, an official reporter is present to record the testimony. After a brief introductory statement by the chairman and often by the ranking minority member or other committee member, the first witness is called. Cabinet officers and high-ranking government officials, as well as interested private individuals, testify either voluntarily or by subpoena. So far as practicable, committees require that witnesses who appear before it file a written statement of their proposed testimony in advance of their appearance and limit their oral presentations to a brief summary thereof. In the case of a witness appearing in a nongovernmental capacity, a written statement of proposed testimony shall include a curriculum vitae and a disclosure of certain federal grants and contracts. Upon request by a majority of them, minority party members of the committee are entitled to call witnesses of their own to testify on a measure during at least one additional day of a hearing. Each member of the committee is provided five minutes in the interrogation of each witness until each member of the committee who desires to question a witness has had an opportunity to do so. In addition, a committee may adopt a rule or motion to permit committee members to question a witness for a specified period not longer than one hour. Committee staff may also be permitted to question a witness for a specified period not longer than one hour. A transcript of the testimony taken at a public hearing is made available for inspection in the office of the clerk of the committee. Frequently, the complete transcript is printed and distributed widely by the committee.

MARKUP

After hearings are completed, the subcommittee usually will consider the bill in a session that is popularly known as the ‘‘markup’’ session. The views of both sides are studied in detail and at the conclusion of deliberation a vote is taken to determine the action of the subcommittee. It may decide to report the bill favorably to the full committee, with or without amendment, or unfavorably, or without recommendation. The subcommittee may also suggest that the committee ‘‘table’’ it or postpone action indefinitely. Each member of the subcommittee, regardless of party affiliation, has one vote. Proxy voting is no longer permitted in House committees.

FINAL COMMITTEE ACTION

At full committee meetings, reports on bills may be made by subcommittees. Bills are read for amendment in committees by section and members may offer germane amendments. Committee amendments are only proposals to change the bill as introduced and are subject to acceptance or rejection by the House itself. A vote of committee members is taken to determine whether the full committee will report the bill favorably, adversely, or without recommendation. If the committee votes to report the bill favorably to the House, it may report the bill with or without amendments. If the committee has approved extensive amendments, the committee

may decide to report the original bill with one ‘‘amendment in the nature of a substitute’’ consisting of all the amendments previously adopted, or may introduce and report a new bill incorporating those amendments, commonly known as a ‘‘clean’’ bill. The new bill is introduced (usually by the chairman of the committee), and, after referral back to the committee, is reported favorably to the House by the committee. A committee may table a bill or fail to take action on it, thereby preventing its report to the House. This makes adverse reports or reports without recommendation to the House by a committee unusual. The House also has the ability to discharge a bill from committee. For a discussion of the motion to discharge, see Part X. Generally, a majority of the committee or subcommittee constitutes a quorum. A quorum is the number of members who must be present in order for the committee to report. However, a committee may vary the number of members necessary for a quorum for certain actions. For example, a committee may fix the number of its members, but not less than two, necessary for a quorum for taking testimony and receiving evidence. Except for the Committees on Appropriations, the Budget, and Ways and Means, a committee may fix the number of its members, but not less than onethird, necessary for a quorum for taking certain other actions. The absence of a quorum is subject to a point of order, an objection that the proceedings are in violation of a rule of the committee or of the House. Committees may authorize the chairman to postpone votes in certain circumstances.

POINTS OF ORDER WITH RESPECT TO COMMITTEE HEARING PROCEDURE

A point of order in the House does not lie with respect to a measure reported by a committee on the ground that hearings on the measure were not conducted in accordance with required committee procedure. However, certain points of order may be made by a member of the committee that reported the measure if, in the committee hearing on that measure, that point of order was (1) timely made and (2) improperly disposed of.

VII. REPORTED BILLS

If the committee votes to report the bill to the House, the committee staff writes a committee report. The report describes the purpose and scope of the bill and the reasons for its recommended approval. Generally, a section-by-section analysis sets forth precisely what each section is intended to accomplish. All changes in existing law must be indicated in the report and the text of laws being repealed must be set out. This requirement is known as the ‘‘Ramseyer’’ rule. A similar rule in the Senate is known as the ‘‘Cordon’’ rule. Committee amendments also must be set out at the beginning of the report and explanations of them are included. Executive communications regarding the bill may be referenced in the report.

If at the time of approval of a bill by a committee other than the Committee on Rules a member of the committee gives notice of an intention to file supplemental, minority, or additional views, all members are entitled to not less than two additional calendar days after the day of such notice (excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays unless the House is in session on those days) in which to file those views with the clerk of the committee. Those views that are timely filed must be included in the report on the bill. Committee reports must be filed while the House is in session unless unanimous consent is obtained from the House to file at a later time or the committee is entitled to an automatic filing window by virtue of a request for views. The report is assigned a report number upon its filing and is sent to the Government Printing Office for printing. House reports are given a prefix-designator that indicates the number of the Congress. For example, the first House report filed during the 110th Congress was numbered 110–1.

In the printed report, committee amendments are indicated by showing new matter in italics and deleted matter in line-through type. The report number is printed on the bill and the calendar number is shown on both the first and back pages of the bill. However, in the case of a bill that was referred to two or more committees for consideration in sequence, the calendar number is printed only on the bill as reported by the last committee to consider it. For a discussion of House calendars, see Part IX. Committee reports are perhaps the most valuable single element

of the legislative history of a law. They are used by the courts, executive departments, and the public as a source of information regarding the purpose and meaning of the law.

CONTENTS OF REPORTS

The report of a committee on a measure must include: (1) the committee’s oversight findings and recommendations; (2) a statement required by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, if the measure is a bill or joint resolution providing new budget authority (other than continuing appropriations) or an increase or decrease in revenues or tax expenditures; (3) a cost estimate and comparison prepared by the Director of the Congressional Budget Office; and

(4) a statement of general performance goals and objectives, including outcome-related goals and objectives, for which the measure authorizes funding. Each report accompanying a bill or joint resolution relating to employment or access to public services or accommodations must describe the manner in which the provisions apply to the legislative branch. Each of these items is set out separately and clearly identified in the report. With respect to each record vote by a committee, the total number of votes cast for, and the total number of votes cast against any public measure or matter or amendment thereto and the names of those voting for and against, must be included in the committee report. This requirement does not apply to certain votes taken in the Committees on Rules and Standards of Official Conduct. In addition, each report of a committee on a public bill or public joint resolution must contain a statement citing the specific powers granted to Congress in the Constitution to enact the law proposed by the bill or joint resolution. Committee reports that accompany bills or resolutions that contain federal unfunded mandates are also required to include an estimate prepared by the Congressional Budget Office on the cost of the mandates on state, local, and tribal governments. If an estimate is not available at the time a report is filed, committees are required to publish the estimate in the Congressional Record. Each report also must contain an estimate, made by the committee, of the costs which would be incurred in carrying out that bill or joint resolution in the fiscal year reported and in each of the five fiscal years thereafter or for the duration of the program authorized if less than five years. The report must include a comparison of the estimates of those costs with any estimate made by any Government agency and submitted to that committee. The Committees on Appropriations, House Administration, Rules, and Standards of Official Conduct are not required to include cost estimates in their reports. In addition, the committee’s own cost estimates are not required to be included in reports when a cost estimate and comparison prepared by the Director of the Congressional Budget Office has been submitted prior to the filing of the report and included in the report. It is not in order to consider bills and joint resolutions reported from committee unless the report includes a list of congressional earmarks, limited tax benefits and limited tariff benefits in the bill or in the report (including the name of any Member, Delegate or Resident Commissioner who submitted a request to the committee for each respective item included in such list) or a statement that the proposition contains no such congressional earmarks, limited tax benefits, or limited tariff benefits.

FILING OF REPORTS

Measures approved by a committee are to be reported by the chairman promptly after approval. If not, a majority of the members of the committee may file a written request with the clerk of the committee for the reporting of the measure. When the request is filed, the clerk must immediately notify the chairman of the committee of the filing of the request, and the report on the measure must be filed within seven calendar days (excluding days on which the House is not in session) after the day on which the request is filed. This does not apply to a report of the Committee on Rules with respect to a rule, joint rule, or order of business of the House or to the reporting of a resolution of inquiry addressed to the head of an executive department.

AVAILABILITY OF REPORTS AND HEARINGS

A measure or matter reported by a committee (except the Committee on Rules in the case of a resolution providing a rule, joint rule, or order of business) may not be considered in the House until the third calendar day (excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays unless the House is in session on those days) on which the report of that committee on that measure has been available to the Members of the House. This rule is subject to certain exceptions including resolutions providing for certain privileged matters and measures declaring war or other national emergency. A report of the Committee on Rules on a rule, joint rule, or order of business must lay over for one legislative day prior to consideration. However, it is in order to consider a report from the Committee on Rules on the same day it is reported that proposes only to waive the availability requirement. If hearings were held on a measure or matter so reported, the committee is required to make every reasonable effort to have those hearings printed and available for distribution to the Members of the House prior to the consideration of the measure in the House. Committees are also required, to the maximum extent feasible, to make their publications available in electronic form. A general appropriation bill reported by the Committee on Appropriations may not be considered until printed transcripts of committee hearings and a committee report thereon have been available to the Members of the House for at least three calendar days (excluding Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays unless the House is in session on those days).

VIII. LEGISLATIVE OVERSIGHT BY STANDING

COMMITTEES

Each standing committee, other than the Committee on Appropriations, is required to review and study, on a continuing basis, the application, administration, execution, and effectiveness of the laws dealing with the subject matter over which the committee has jurisdiction and the organization and operation of federal agencies and entities having responsibility for the administration and evaluation of those laws.

The purpose of the review and study is to determine whether laws and the programs created by Congress are being implemented and carried out in accordance with the intent of Congress and whether those programs should be continued, curtailed, or eliminated. In addition, each committee having oversight responsibility is required to review and study any conditions or circumstances that may indicate the necessity or desirability of enacting new or additional legislation within the jurisdiction of that committee, and must undertake, on a continuing basis, future research and forecasting on matters within the jurisdiction of that committee. Each standing committee also has the function of reviewing and studying, on a continuing basis, the impact or probable impact of tax policies on subjects within its jurisdiction. The rules of the House provide for special treatment of an investigative or oversight report of a committee. Committees are allowed to file joint investigative reports and to file investigative and activities reports after the House has completed its final session of a Congress. In addition, several of the standing committees have special oversight responsibilities. The details of those responsibilities are set forth in the rules of the House.

IX. CALENDARS

The House of Representatives has four calendars of business: the Union Calendar, the House Calendar, the Private Calendar, and the Calendar of Motions to Discharge Committees. The calendars are compiled in one publication printed each day the House is in session. This publication also contains a history of Senate-passed bills, House bills reported out of committee, bills on which the House has acted, and other useful information. When a public bill is favorably reported by all committees to which referred, it is assigned a calendar number on either the Union Calendar or the House Calendar, the two principal calendars of business. The calendar number is printed on the first page of the bill and, in certain instances, is printed also on the back page. In the case of a bill that was referred to multiple committees, the calendar number is printed only on the bill as reported by the last committee to consider it.

UNION CALENDAR

The rules of the House provide that there shall be:

A Calendar of the Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union, to which shall be referred public bills and public resolutions raising revenue, involving a tax or charge on the people, directly or indirectly making appropriations of money or property or requiring such appropriations to be made, authorizing payments out of appropriations already made, releasing any liability to the United States for money or property, or referring a claim to the Court of Claims. The large majority of public bills and resolutions reported to the House are placed on the Union Calendar. For a discussion of the Committee of the Whole House, see Part XI.

HOUSE CALENDAR

The rules further provide that there shall be:

A House Calendar, to which shall be referred all public bills and public resolutions not requiring referral to the Calendar of the Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union.Bills not involving a cost to the government and resolutions providing special orders of business are examples of bills and resolutions placed on the House Calendar.

PRIVATE CALENDAR

The rules also provide that there shall be:

A Private Calendar, . . . to which shall be referred all private bills and private resolutions.

All private bills reported to the House are placed on the Private Calendar. The Private Calendar is called on the first and third Tuesdays of each month. If two or more Members object to the consideration of any measure called, it is recommitted to the committee that reported it. By tradition, there are six official objectors, three on the majority side and three on the minority side, who make a careful study of each bill or resolution on the Private Calendar. The official objectors’ role is to object to a measure that does not conform to the requirements for that calendar and prevent the passage without debate of nonmeritorious bills and resolutions. Alternative procedures reserved for public bills are not applicable to reported private bills.

CALENDAR OF MOTIONS TO DISCHARGE COMMITTEES

When a majority of the Members of the House sign a motion to discharge a committee from consideration of a public bill or resolution, that motion is referred to the Calendar of Motions to Discharge Committees. For a discussion of the motion to discharge, see Part X.

X. OBTAINING CONSIDERATION OF MEASURES

Certain measures, either pending on the House and Union Calendars or unreported and pending in committee, are more important and urgent than others and a system permitting their consideration ahead of those that do not require immediate action is necessary. If the calendar numbers alone were the determining factor, the bill reported most recently would be the last to be taken up as all measures are placed on the House and Union Calendars in the order reported.

UNANIMOUS CONSENT

The House occasionally employs the practice of allowing reported or unreported measures to be considered by the unanimous agreement of all Members in the House Chamber. The power to recognize Members for a unanimous-consent request is ultimately in the discretion of the Chair, and recent Speakers have issued strict guidelines on when such a request is to be entertained. Most unanimous- consent requests for consideration of measures may only be entertained by the Chair when assured that the majority and minority floor and committee leaderships have no objection.

SPECIAL RESOLUTION OR ‘‘RULE’’

To avoid delays and to allow selectivity in the consideration of public measures, it is possible to have them taken up out of their order on their respective calendar or to have them discharged from the committee or committees to which referred by obtaining from the Committee on Rules a special resolution or ‘‘rule’’ for their consideration. The Committee on Rules, which is composed of majority and minority members but with a larger proportion of majority members than other committees, is specifically granted jurisdiction over resolutions relating to the order of business of the House. Typically, the chairman of the committee that has favorably reported the bill requests the Committee on Rules to originate a resolution that will provide for its immediate or subsequent consideration. If the Committee on Rules has determined that the measure should be taken up, it may report a resolution reading substantially as follows with respect to a bill on the Union Calendar or an unreported bill:

Resolved, That at any time after the adoption of this resolution the Speaker may,

pursuant to rule XVIII, declare the House resolved into the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union for the consideration of the bill (H.R.lll) entitled etc. The first reading of the bill shall be dispensed with. After general debate, which shall be confined to the bill and shall not to exceed lll hours, to be equally divided and controlled by the chairman and ranking minority member of the Committee on lll, the bill shall be read for amendment under the five-minute rule. At the conclusion of the consideration of the bill for amendment, the Committee shall rise and report the bill to the House with such amendments as may have been adopted, and the previous question shall be considered as ordered on the bill and amendments thereto to final passage without intervening motion except one motion to recommit with or without instructions.

If the measure is on the House Calendar or the recommendation is to avoid consideration in the Committee of the Whole, the resolution might read as follows: